Some

related headresses of the 15th Century: theories on construction

Some

related headresses of the 15th Century: theories on construction

Some

related headresses of the 15th Century: theories on construction

Some

related headresses of the 15th Century: theories on construction

I'm going to make some sweeping generalizations here, and illustrate

them with contemporary illustrations. This is a working theory,

so

feel free to drop me a note with other ideas.

From about 1400-1470, women's hats exploded into a wide variety

of shapes, sizes, and materials. There were the simple

stuffed-rolls.

Sometimes these were on top of heart-shaped

pieces at the temples or over the ears; sometimes they were worn

plain

on the head, with the hair in

a braid down the back, or with dags, veils, etc. Upper middle

class women (rich merchan's wives and so forth) arranged their hair, or

used cauls, in little lumps,

bumps, or horns at their temples, covered with ruffled

veils. Toward the middle of the century (1430-1460),

noblewomen

were switching to truncated-cone

and butterfly hats, often

with

ornate decoration and complex veiling. Around 1470, styles seemed

to be in a free-for-all; there is one portrait with cauls,

a roll, and a truncated cone. For some formal and

allegorical

uses, women were still wearing sideless

surcoats and complex rigid hats that covered their ears, but much

of

the noblewomen were switching to a style which is fairly clearly proto-tudor;

smooth square-necked bodices, and lower cone or truncated-cone hats

with

black

(velvet?) lappets, which probably developed into the French hood.

Let's look at some pictures.

Campin's portrait of a young

woman, 1420 and also VanderWeyden's

portrait of a woman, 1435

Things to note: several layers of linen, layered over head, and pinned

to headdress structure. Cauls are not seen but are inferred -

although

they could be hair-buns hiding under there. Few women have enough

hair, of sufficient thickness, to achieve the volume in the later

picture,

so I think that the hair is either augmented, or there is a rigid horn

hidden by the linen. Here's a short

article

about an attempt at this hat.

A similar veil wrapped around

the head, 1425 by Campin

This is a religious figure that appears to have a very similar

headdress

to the 'young woman.' Note how long the veil-tails are. The

lady in the yellow kirtle's braid hangs straight down her back --

implying

that her hair is not up under the headdress. (Here's another of

the

braid going straight down: Woman

from Cologne, 1440 ) The Weyden deposition below (and another one I

have not pictured) shows braids wrapped around the head

circlet-fashion.

Some of these veils, worn long, show ruffles like the Arnolfini and

Mrs.

VE portraits, below.

Arnolfini bride, 1434.

(Pictured above)

Close up of

caul

This one is rather well known. Ruffled veil edges - five layers,

smooth brown caul with tiny braid at perimeter. Is the braid

hair?

Is it silk? Some of the netted hats that can be found have

backgrounds

that are clearly fabric; the colors are not those of hair, and there

are

wrinkles and such. (As a side note, the man's hat in the

Arnolfini

portrait is of black straw; this can be seen in very good

reproductions,

or, of course, on the original in London.)

Deposition from the cross 1435

Weyden- veil of similar type

VanEyck's wife, 1439. (and) Closeup

of caul - note that she gets more layers (seven or eight) than

Mrs.

Arnolfini. Also, the caul has a darker pattern of brown or black

on it. Is it embroidery or fabric? Is it basketry? Some

other

stiff, woven stuff? There is also a perimeter braid, but it looks

rather similar to some types of modern upholstery braid or

soutache.

It is also far more clear that the veil is folded to make the layers;

note

the lowest point on her right sholder where the ruffle is splayed

out.

Nice red wool houppelande with fur lining.

St. Eligius and the Lovers 1449,

Christus

(and) Close view of

caul. This caul is even more unusual; the 'ears' have grown

quite

tall. You can see straight, pearl-headed pins stuck in the tops

of

the cauls, to hold the veil up. Note the net-and-pearls on the

cauls,

and that the cap portion is of a similar color, but a different

pattern.

The cauls are edged with black, and pearls or beads sewn along this

edging.

Portrait of a lady 1460 by

VanderWeyden

This is the portrait that really looks as if the hat is made of some

kind

of basketwork. Not "a basket" but "basketwork," meaning woven or

braided reeds, grasses, shaved woods, or other stiff materials. A

straw hat of the modern sort is basketwork, even if it is not a basket

per se. I have finally seen this hat in persion at the National

Gallery

and it may be that she has masses of blonde hair covered by a thin silk

cover with a basketweave pattern. However, even in the original,

2 feet in front of my eyes, it is impossible to say either way.

Butterfly henin (also pictured

above) Note: The top of the base-hat cannot be seen.

The

general shape is either a gentle cone or completely cylindrical.

There is a perimeter line of black, with a forehead loop; a feature

often

seen, but not always seen. The wires which must exist to hold the

many folds of the veil cannot be seen. There is no chin-strap

pictured;

the hat must stay on by some other means. This woman is also

wearing

a thin-stranded necklace; this sort is often seen along with the

"burgundian"

gown she wears. Some illustrations seem to show that this is

fancy

beading.

Another butterfly henin. On

this one, you can see the inner shape of the base-hat; it is a tall,

truncated

cone. There is a chevron pattern in the fabric covering the

cone.

The veil is transparent.

Donor, 1455 A much shorter

'truncated cone.' This one may be rounded at the tip.

It

is covered in elaborate beading in a diaper (diamond) pattern.

The

perimeter edging on this one is patterned instead of being black, and

there

is an extension of the hat that loops under the ear. This

squared-off-loop

may well be strongly wired so that it can 'catch' the ear in order to

hold

the hat on. The loop disappears up over the top of the hat; it

may

be entirely separate from the hat and gets pinned in place before the

veil

is put on; it may also be adjustable for tension. The veil is

transparent.

Clarice de Gasconne,

1468.

This one could be one of the stuffed-roll hats taken to extremes, or it

could be a stiff truncated cone like these other examples. At any

rate, note that in her attendents, there are two ladies wearing

truncated

cones, and another in a stuffed-roll type hat. This is also

one of the more rare times when you get to see that the women wear

pointy

shoes, too.

The "Roses" tapestry.

This is a composite picture of four of the women from the tapestry; two

have butterfly henins and two have the stuffed roll with cauls and

liripipe

sort of hat.

Women from a family tree, 1471.

Note the "headband" like thingy on the top right, with a forehead

loop.

Could this be the base to some of these fashions?

Note that for truncated cones and full cones, the length of the hair is hidden under the hat completely; only the smoothed hair along the head can be seen.

Even stranger hats:

Mary de Bourgone - note

that the veil is under the ear-cauls; you can see the fold angle just

forward

and under the ear. The hair comes out, ponytail fashion, from the

top of the truncated cone. I did a

version

of this in white with green bits instead of the brown/orange.

It's

a lot of fun to wear.

Dame Nature(1500s; no better date)

Likely

to be somewhat allegorical; reticulated headress with hair down the

back.

St. Barbara (1500s; no better

date) Also likely to be somewhat allegorical (and therefore

slighly

suspect for accuracy.) With hair down the back.

Based on the picturs above, I believe that the cauls are not elaborately arranged hair; they are shaped items. My version pictured above (in the black dress) is straw basketry (like a straw hat) covered with brown wool to match my hair. This shape is easy to put on and keep on; bobby pins on the cauls, a stabilizing ribbon between the cauls, and pinning my braids around the base (as the thin braids are arranged in the original) result in a strong structure on which to pin the veil.

I also made an attempt (many years ago) at the St. Elegius type of caul, which I made out of buckrum. The result pleased me at the time, although I no longer wear it because it falls short in many areas. It was helpful as an educational experience.

Veils, ruffled:

There are two theories I have encountered about the ruffled veils; either in books, or in conversations with others both in and out of the field. One is that they were woven with extra shuttle passes in the selveges, to produce extra fabric compared with the main body of the veil. Another theory is that the ruffles were sewn onto already-created yardgoods. A third is that the fabric was somehow stretched on the selvedge to produce the ruffles -- or that the main body of the veil was shrunken.

For my version (see picture), I opted for the "sewn on later" theory. The veil is thin cotton, about 12 feet long, with twill-tape pleated and sewn onto the edges. It is then folded up as if it were one much shorter veil, and pinned over the cauls. It falls in much the same manner as the picture, although next time I will try either a very, very fine cotton, or a silk; the cotton as it exists is too thick, and I think a little to weighty, to be comfortable.

Because even the thin cotton is so thick and heavy, I am fairly sure

that these ruffled veils were of silk. If they were of silk, the

shrinkage theory would not produce enough fullness, so we're left with

the special-weaving theory and the sewn-on theory.

This segment has also been split off into a separate handout using the method I've found most successful, that of antenna-like wires coming up from the top of the hat, and then angling forward to support the veil. I reproduce it below, but the separate page might be best if you want something that's easy to print out.

So how do you make one of these? The simplest method is based on some reasonable "educated guesses."

We know that around this time, some men wore fancy, woven straw hats -- the Arnolfini Wedding painting by Van Eyck, 1434, shows the groom in a black straw hat; look at the very top on a good reproduction, and you can see the weave. Some were wearing shaped felt hats. Van der Weyden's Portrait of a Lady from 1460 looks as if the hat is actually some sort of uncovered basketry.

We know that these hats needed to be both stiff and lightweight. Janet Arnold's book about Elizabethan costuming shows how many corsets were constructed with reeds bundled up as the stiffening. Why not use reeds for stiffening hats at an earlier age? They are lightweight, easy to shape, easy to obtain. Most of my hats are basketry, although stiff wool felting is another strong, light contender for material.

Using woven straw or baskets is what is generally termed "conjecturally accurate." This means that the materials are all ones that the medieval people had access to; they had the skills to make them; they used something like this in other areas of life (baskets, men's hats); and there are no examples that directly conflict with the use of the material or technique in this way. Of course, with hats of this period, since we have exactly Zero extant examples, it's very hard to say what they really did.

Making a truncated cone:

The great thing about this working theory is that you can get basket or woven-straw cache-pots for houseplants in the right sizes for a truncated-cone hat, at any garden store or at rummage sales. Using these as a base produces a lightweight hat which will flex to your head, and help hold itself on based on that flex. Sure, you'll get a few odd looks, putting baskets on your head in the store, but once you get them covered, you'll be pleased with the results.

If you go shopping for a basket in order to make this sort of hat, you will have two types of materials to choose from. Flat grasses, woven tightly into plant cache-pots, or thin, flexible, brown reeds, usually in larger loops and weaves. Be certain that the size is large enough to fit over your head at your hairline, and down the back of your head behind your ears, and does not fall off too easily when you move your head. It will need to be a bit loose, to give you some room for the fabric and lining you will cover it with.

Take your basket home, take out any plastic lining that might be inside of it. Dust it off or wash it if needed, and let dry. Mark a line on the outside from the open side to what used to be the flat bottom (and will now be the flat top); using this line as a position-marker, slowly roll the basket across your covering fabric, making marks every few inches, so that you can cut out a piece of fabric which will fit smoothly to your hat. This will look like a thick arc of fabric. Add seam allowances, and cut out. Also cut out a circle that is a bit larger than the top of the hat. The covering fabric can then be sewn together in a angled cylinder. Sew the round bit for the top of the hat to the narrow end, so that you have a cover which will fit smoothly over your straw basket. It can be pulled over the hat like a strangely-shaped pillowcase, and basted to the basket, folding over the edge that will go against your head, to the inside, so that it looks smooth. The lining works the same way.

You may make a small black velvet loop for over your forehead if you wish, but not all of these hats have them.

Wires and veils:

You'll notice that we cannot see any way for the veil to be supported in the picture from the Roses Tapestry. I have a couple dozen pictures of this sort of hat, and all of them seem to be held up by magic. This is a darn nuisance for those of us interested in an accurate recreation! The support may be hidden by the veiling, or left out of the pictures for aesthetic reasons. Simple starching of the veils would not allow the heights these rise to.

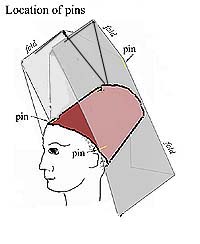

The easiest way to get this shape seems to be wires, positioned like ant antennae. The double set of veils in the Roses Tapestry would require two sets of these, one higher than the other. One or more rectangular veils are folded over these in an 'M' shape, and pinned to the wire. Some butterfly hats seem to have only one layer.

The Roses Tapestry women seem to have versions of these at least two feet high. I would advise making a smaller one first, and putting larger wires on after you get used to it.

Find

a thin coat hanger, and cut off the hook and the twisted neck, and

shape

it into a smooth V. Bend the "antennae" over, halfway up (see fig

2). The point of the wire V gets sewn to the flat back of the truncated

cone. A coat hanger will produce enough wire for a foot high

version.

Find

a thin coat hanger, and cut off the hook and the twisted neck, and

shape

it into a smooth V. Bend the "antennae" over, halfway up (see fig

2). The point of the wire V gets sewn to the flat back of the truncated

cone. A coat hanger will produce enough wire for a foot high

version.

As mentioned, most veils are probably of very thin and transparent silk, although I have heard it argued that linen can be made "nearly transparent." Both ironed linen and natural silk can attain the stiffness shown, although I'm not certain that linen would be able to be as stiff as silk when you consider the yardage needed for some of the butterfly veils, because it is heavier. Stiff polyester organza would also work, and is the best choice if you're not somewhere that you can get silk. To get the right shape, you can use tulle or netting for a draft -- drape it until it pleases you, and then use it as a pattern to cut your real veil. For my rather short version of a butterfly hat I needed a piece of thin stiff silk two yards long and two feet wide.

The

veil is draped over the wires, pinned down to the hat in the valley

between

the wires making an "M" shape. Use a straight pin on each wire at

the bend in the wire where the fabric folds over it, to anchor the veil

to the wire. You could baste this if you prefer. A pin

where

the veil touches the side of the cone, near your temples, will help

keep

it stable without making it look too tensioned over the wires.

The

veil is draped over the wires, pinned down to the hat in the valley

between

the wires making an "M" shape. Use a straight pin on each wire at

the bend in the wire where the fabric folds over it, to anchor the veil

to the wire. You could baste this if you prefer. A pin

where

the veil touches the side of the cone, near your temples, will help

keep

it stable without making it look too tensioned over the wires.

The veil will fall oddly in the back unless you put in at least one pin to be sure the folds cover the top/back of the cone. Don't give in to the impulse to pin it down everywhere -- it needs to have some movement, and if the fabric is stiff, it will fall in the shapes we see in the medieval illustrations.

Some of the thin veils appear to have either fold lines or seam lines painted on; if you have to make your veil out of more than one piece of fabric, that's ok. The veil itself rarely goes below the shoulder or mid-upper-back level; all the fabric is suspended above.

There are three examples that I know of that have beading on an

edge of a veil (for the entire medieval period), and they are all from

this time period. One is an elaborately

beaded headdress from Florence, and two others are on Italian

women;

one a single portrait with an

opaque

veil, and the other many

young

women with transparent veils. However, none of these are with

the butterfly style, so I would advise avoiding too much weight on your

veil.

Some other illustrations that might be of interest:

Hats from the Devonshire Hunting

Tapestries with cauls and some with veils.

Strange hat, 1410, fancy silk (?)

houp. Note that the hair seems to be showing in the usual 'caul'

location.

If you want to start off with an easier project, try the "Quick and easy caul" article. See other articles for more pictures.

Similar to both cauls and cone type hats is the reticulated headdress.

Further reading about cone hats (see the general Further Reading page for other items):

Great illustrations of period paintings and illuminations:

Sally Fox and Belle Tuten, The Medieval Women: An Illuminated

Calendar

-- multiple ISBNs, as they come out yearly. Unfortunately can not

be bought once calendar-season is over, but lots of SCA folk have them

and save them. Truncated-cone pictures can be found on these

pages:

1/92, 12/92, 3/96, 6/97, 7/97, 12/97, 3/98, 6/98 -- which has a good

enough

version of the Arnolfini that you can see the straw hat, 7/98, 7/99 --

this one has a ponytail coming out the *top* of the hat! , 11/00.

The medieval costuming articles on my web pages have many scans from

this

source, if you do not have access to it.

For pictures, diagrams, and descriptions of some items which have

been

dug up from this time (lots of fascinating stuff):

Geoff Egan and Frances Pritchard, Dress Accessories c. 1150-1450:

Medieval finds from excavations in London, ISBN 0-11-290444-0;

pages

291-296 for headwear.

Reeds as used in costume, extant garments, and general

techniques

for 100 years later than these hats:

Janet Arnold, Patterns of Fashion: The cut and construction of

clothes

for men and women c.1560-1620, ISBN 0-333-38284-6

For an overview of this era with lots of drawings, the following

book

is very useful. However, be aware that some of his conclusions

seem

to be utterly unsupportable from the references for them that he gives;

before taking anyting as gospel, look up his source. With that

caveat,

it's a good book to look through for inspiration before going to more

narrowly-focused

sources:

Herbert Norris, Medieval Costume and Fashion, ISBN

0-486-40486-2.

Note that this is the 1999 Dover Edition, which claims to be an

unabridged

version of his 1927 book Costume & Fashion, Volume 2: Senlac to

Bosworth, 1066-1485

| All material © 2000 - 2001 Cynthia Virtue | Email Author with comments |

| Back to Virtue Ventures Main Page | Back to Article Index |