A theory on construction of the Houppelande:

Cynthia Virtue's rotated-corner,

circle plan houppelande

Note that there are many

pictures, which will take a while to load. Most small pictures

link to larger versions.

by Cynthia du Pré Argent

© 2000 Cynthia Virtue

Introduction

This is a summary of work on a rotated-corner full-circle plan

houppelande, as sent to the Historic Costume email list. I

discussed this theory with them in the summer of 1998, and then

constructed the black and red houppelande to test the pattern. In

late

winter of 2000, I made a men's version for my husband. In

the autumn of 2001, I made one for

myself.

I am proud of my hypothesis about the houppelande

construction; it

is original work. The best thing though, is that it looks like it

is

supposed to! It is not

the same idea as the traditional circle houppelande which is like a

circle with a hole cut in it for the head.

This is a long page. You may want to jump to:

|

|

Medieval Sources

Any theory is only as good as the results produced from it, so here are

versions of the medieval artworks that informed their construction, and

photos of the garments I made. Some of the images in the table

link to larger versions.

Medieval sources

| Man and woman, drawn from the Devonshire Hunting Tapestries,

1420. Note how full the hem of the man's garment is, and how his

belt hovers around his hips. Magically. Note the V neck in

front, edged with fur like the hem. Here's a picture of the orginal

tapestry section, showing three people with one decorated sleeve. (Unless

the guy in the background has a decorated hood; I can't tell.) |

|

| Albert of Bavaria, from the tomb of Isabella of Bourbon

(these statues were formerly identified as "the Dam chimneypiece" |

|

| Men at a ceremony; note that the pleats run from the waist to

the shoulders, not toward the neck |

|

| Lorenzo de Medici; his pleats do seem to go toward the neck. |

|

| Servers of high rank. Note the V neck in back, with the

pourpoint collar showing above it. |

|

| Another tracing, this one from The Roses Tapesty |

|

Garments

The garments I've made

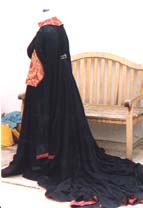

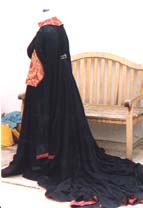

| First draft women's houp. Another one will be along

shortly in green wool challis. View of this black one, from the front. |

|

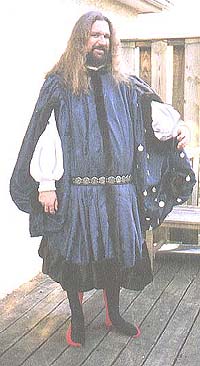

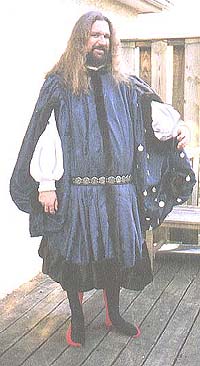

Houp for my husband, Lord Francois Thibault.

Wrist openings and slit sleeve.

Blue cotton damask, edged with brown false fur (like the sort that Gund

uses; very pettable.)

Silver colored mounts on one sleeve only; belt loops to hold up belt

magically at hips.

Hook tape to fasten center front.

Hem is about 9 yards; the whole garment used 10 yards of 54"

fabric. It weighs about 10 pounds, but as all the weight is

spread across the shoulders, he reports that it is very comfy.

These are not the normal hose. |

|

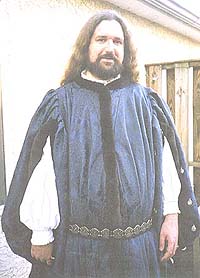

| Another view. Note that pleats in the body head toward

shoulders. |

|

| Arms through the slits, this time. He should have a

pourpoint over his shirt, but I haven't made him one yet. |

|

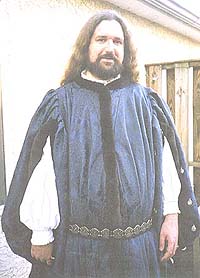

| Closer view. Note the V-neck seam in the larger version

-- this is the edge of the selvedge of the quarter-circle. |

|

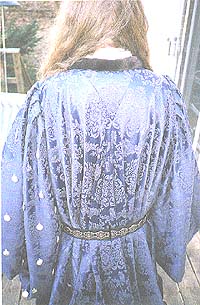

| Back view of V-neck portion, and nice pleats. Pleats

are only tacked down to a ribbon at belt level; this is a natural lie

over the top of his back. |

|

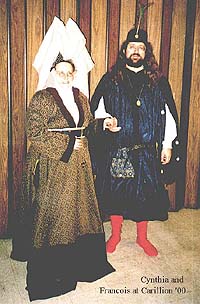

| Both of us at a recent event 3/00. My houp is not of

this plan; the butterfly hat finally

makes

me taller than him!. To get the "no shoe" effect from the

medieval pictures, we dyed white canvas slippers to match his hosen. |

|

Common Houppelande Theories

As far as I, and I believe others on this list know, there are no

extant houppelandes. Nor any pattern books nor tailor's notes nor

household accounts from the time (15th century) that discuss

construction. I'd love to hear any leads for either of

these. [There is a "robe of Charles the Bold" from 1476, which

has a close fitted upper body connected to a gathered, pieced "skirt"

but this is more in keeping with the later women's "Burgundian"

houppelande style. A 16th century Tailor's Book has a Doctors'

Robe that has a partial-circle construction.]

Given that, there are a lot of theories about how they really did

it. The

pattern that we see most often is like a modern dress; relatively

closely cut neck, shoulder and arm, and then a wide angle going to the

hemline from under the arm. The trouble with this is that many of

the illustrations show fullness/pleats pointing toward the shoulder

line, and this does not give that effect; at best, the pleats head

toward the neck.. For example, I think Hunnisett's version gets

pleats headed in the direction of the shoulders, but they lose fullness

too soon to make it past the breasts. (There may well have been

several methods of cutting these, and in my opinion, if you can get

lots of pleats out of it at the bust and waist, without having the

pleats reach the shoulder seam, you're on the right track.)

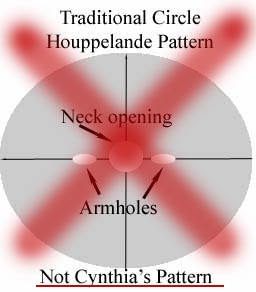

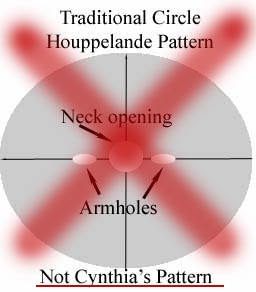

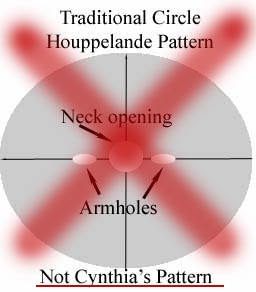

Another option is diagrammed on the right; the circle houp with a

hole for the head.

Another theory is that, like the earlier tunics, the fullness was

made entirely by a multitude of triangular gores. If these gores

started above the bust, the fullness would of course extend in the

direction of the cut for the gores. But what ultimate shape to

aim for? One like a modern dress? Or something else?

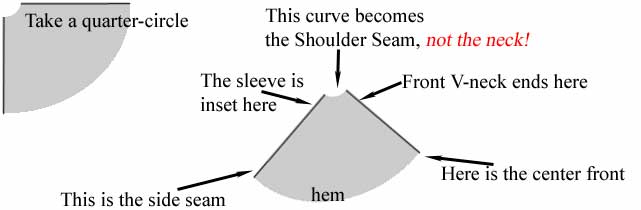

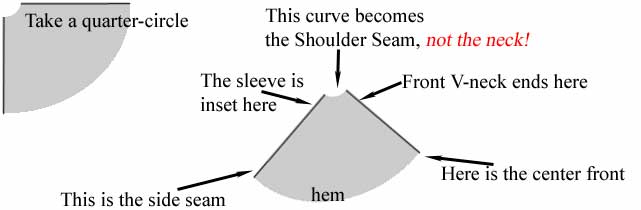

A New Theory: Cynthia's rotated-point quarter

circle

My theory that I tested is that some versions

of the houppelande were made with 4 quarter-circle panels, like a

pieced circle skirt -- but that the "center" curve of the panel was at

the shoulder seam, not at the neck.

| Think of a woman's circle-cut skirt. It is often made

of four panels, each a quarter circle, with a curved "bite" cut out of

the top, where it attaches to the waistband. |

Click

on all of these to get larger, readable versions. Click

on all of these to get larger, readable versions. |

| The folds of the full skirt head toward the waistband,

because it is there that the center of the piece of fabric is lifted up

relative to the rest of the fabric. The folds go towards the

straightened curve. |

|

| Now consider a full-circle houppelande with the center of the

circle at the neck. (But with that same curve cut out, like for a

circle skirt.) The folds will either head toward the neck, or

they won't really be there at all, because the fabric has not been

pulled up to create the stress lines that are reflected in what we see

as folds. This version does produce a lot of fullness at the hem

(good) but doesn't explain the V-necks we see in most pictures (bad.) |

(Not CV's) (Not CV's)

|

So where do we want our pleats to go? Toward the

shoulder. How do we get them going there? By "pulling up"

fabric into a line perpendicular to gravity. What's the closest

thing to a perpendicular line at the top of a human? The

shoulder. The curved "bite" of the quarter-circle panel that is

similar to the waistline of a circle skirt, becomes the shoulder

seam. This makes the selvedges run from the side of the neck to

points on the center front and center back of the garment. (See the

detail photos above.)

NOTE: I now think there is not

supposed to be any cut-out for the sleeve. It just gets set in, blind.

|

|

So how do you cut this all out? It's fairly

simple, once you understand the method.

What really

helps: Do it for a doll first!

Graph your needed measurments (primary one being the

radius, which is equal to your shoulder-to-hem desired length, plus

whatever hem you want) onto your fabric with a piece of dressmaker's

chalk. As noted here, the CF and CB seams are on the

selvedge. This allows for a train, and for extra distance going

over busts or tummies. If you need more room sideways, join

fabric together parallel to the selvedge. If you're not certain,

cut it out of cheap fabric first and check the drape and hem.

Once you're satisfied, you can cut all four out at once. Then you

just need the triangle inserts (next diagram) for the front and back,

and your sleeves. If you want a train (and some of the women's

did

have longer back sections,) be sure to graph that out before

cutting! When it's put together, belt it in, arrange your pleats

and have someone mark the true hem for you.

NOTE: I've had some problems

with little pointy bits at the outside of the shoulder. This is

solved by having only a slit for the hole for the sleeve, instead of a

curved bite as shown in the tiny diagrams -- I've corrected the large

ones that these link to. More images will be coming soon.

|

Don't forget to click on these tiny

thumbnails to get the larger schematics! Don't forget to click on these tiny

thumbnails to get the larger schematics! |

| Diagram of the triangular sections that are inserted along

the center front and center back, to bring the neckline up to "crew

neck" level. NOTE that these should probably be larger than the

one pictured here. The triangle in front on my newest houp seemed

to be more graceful if it was about a foot tall from neck to mid-chest,

and in back, about 9". See the pictures of the blue man's houp

for proportion. |

|

| Here's the sleeve pattern for the man's houp; it is based on Hunnisett's bag sleeve, but with two

major changes. See this subsidiary page about bad bag-sleeve patterns. |

|

Here's the former schematic

from the first version of this page.

Theory in Practice

This worked to produce narrowing fullness that pointed at the shoulder

line. It also produced some unexpected interesting things.

On men's full outer garments from this period, there is sometimes a

very obvious v-necked seam

across the upper back. The theorized pattern requires a v-necked

seam across the upper back, because the long side of the panels part

ways with each other mid-upper-back, as they head toward the shoulder.

There is the same effect in the front, to a lesser degree. This V

may exist in women's garments, but we rarely see them from the

back. When we do, usually the hair or the hat hides the back of

the neck area. As constructed, there is plenty of fabric to pleat under

the belt (appx. 4 yards) and a hem circumference that is enormous!

If the houppelande had been done with the center curve of the panel

at the neck (instead of at the shoulder), these triangular insets would

not be needed. It is possible that a cut-out second curve on the side

of

the panel at the shoulder line (in the neck-center-point houp) would

re-direct the fullness to the shoulder. I haven't tried that yet.

Hemming: It is

critical to adjust the hemline when the houp it is on the body (or a

dress dummy) after it is nearly completed, and with a belt and

pleats/folds where they are expected. The final hem should be at

the same height all around (unless there is a train for women).

This will require measuring with a yardstick from the ground in the

classic manner, and trimming off some fabric. Women who are

making the houp longer than the ground (mine tend to be a foot longer

than where it hits the ground) will need to stand on something fairly

high while someone else measures the hem.

The hemline is huge! The women's version is a lot of fun to

wear, and we don't have to sweep the hall after an event anymore.

My sweetie said "I finally feel like a real medieval nobleman!"

Other Style Considerations

These houppelandes were done in the style of the Devonshire Hunting

Tapestries. There are some key points that are often missed when

doing a houppelande; if you take just a little care, they'll look

better/more like the sources.

- Fabric choice. A

Houppelande is all about luxurious fabric. Do not bead it.

Do not sew on ribbon type trim. Choose the best fabric you

can, (the modern fabric page and the extant garments page might help you) and even

if

it is cotton poplin, be sure to have plenty of it, in a good strong

color. Some embroidery is appropriate, or decoration on one sleeve with metal shiny bits,

called bezants.

- Belt location & pleats

It is important to put your belt at the right level, or else you

don't get the medieval look. For women, this means just under the

bust -- where the lower band of your bra sits. Men, usually the

waist or a slightly dropped-waist location. The blue man's houp

has black beltloops to keep it in the right spot. Use your

fingers to pleat the fabric under the belt before tightening it all the

way; the belt keeps the pleats in place.

- You're not dressed without a hat.

Other notes on these particular houps:

For the women's, a Peter-pan-like collar, hanging oversleeves to the

knee with a slit in them at about elbow height for the arms to go

through, long train (although at about 3' long, shorter than those in

the tapestries.)

Because the fabric that I did the first version in was cheap and not

very thick (the black with red), the train tends to fold over

itself as it is worn around, but my friends had a lot of fun

pulling it out and arranging it to drape nicely. It was a draft

dress, after all. It's black; the collar and sleeve linings are a

red/gold lattice pattern, and there is a red band at the hem of the

sleeves and the skirt, to imitate a full red lining.

For the man's, I used a cotton damask with about as much body as

chino slacks. The brown fur trim was a fancy fake fur; the

bezants were obtained from The Pillaged Village, and were intended for

middle-eastern bellydance outfits. They look much like the

various mounts dug up from England.

Future Investigations

The fabric was also very wide (60"), so I did not need to piece the

panels. It could be done more plausibly with gores, although there is

some evidence that wider silks were imported from Italy during this

time. A wide fabric would make it easy to do quarter-circle

panels.

One of these days I'm going to sit down with all my pictures of

patterned houppelandes and see if the patterns in the fabric themselves

give any hints as to the orientation of the pattern pieces on the

fabric yardage. This might help with construction questions, IF

the painters were painting from real examples, and replicated the

patterns as they were, not just as artistic license.

Here are some ideas for storing these

heavy garments.

See my further reading page for

some of my picture and text sources.